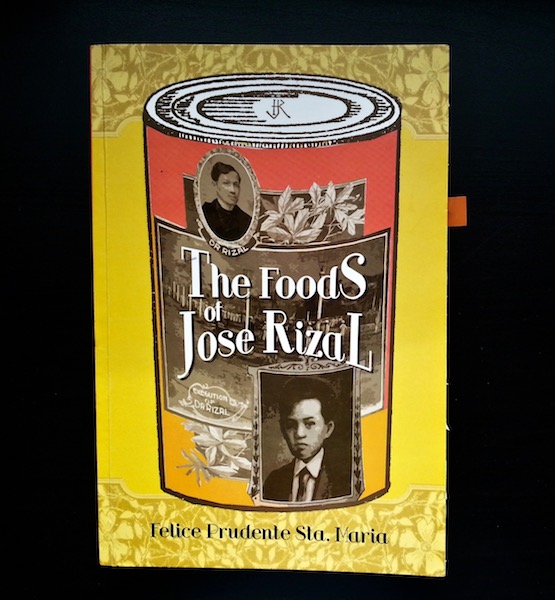

The Foods of Jose Rizal by Felice Sta. Maria

Why does the subject of learning as much as I can about Filipino food - of its history and culture - matter so much to me? It's a question that sneaks up on me when I'm on my way to work, looking across the Toronto skyline from Humber Bay, and permeates my thoughts on my days off, when regular people would think it healthy to practice a few rounds of tennis or shut their brains off at the movies.

I cannot help but keep thinking about Filipino food. I try to cook when I can, but I live a North American lifestyle, where I work 44 hours a week, spend time on transit, run errands, do chores, and try to spend as much time as I can with the people I care about.

I want to learn more because I've discovered that to understand myself, I need to keep exploring my relationship with Philippine food and cooking - what makes it tick, where it comes from, what fuels it, and how it's evolved and continues to develop.

"There are more days than longaniza sausages." - Jose Rizal

To those educated in Philippine high schools: do you recall coming across this line from any of your high school Rizaliana? I sure don't!

Mi Ultimo Adios: My Last Farewell

I never paid attention to Rizal through any of my required literature classes in high school and college. Rizaliana was saved for the ladies at the library and consistently high 90s (A+) students; not the chain-smoking, free-thinking kind of folk I identified strongly with in my teens. I'm coming around the subject, though, and am certainly glad I came across this book to order.

Jose Rizal, for those unfamiliar with the name and above portrait, is the Philippines' national hero. In Felice Prudente Sta. Maria's book I found out that the last poem penned by Rizal, called Mi Ultimo Adios, was stashed away into the millimetre-thin wick holder of a metal food warmer, originally sent by Rizal's family because of a concern that the food sent to his prison chambers arrived cold. History provides amusing facts!

Rizal's childhood and adolescence

I'd love to share some passages from the book, and encourage those interested to please support Philippine literature and purchase a copy of The Foods of Jose Rizal from Anvil Publishing.

"So many nice things to eat were grown and made in the Philippines during Rizal's youth," Sta. Maria writes. "The gardens and orchards of Tondo (a suburb of Manila) furnished markets with mango, common orange, mandarin orange, bananas and other fruit. The coffee from wild plants was said to be of excellent quality. Civet cats were credited for spreading the seeds, voiding what they had eaten. Laguna (a nearby town) was a major source of vegetables and buri palm sugar enjoyed at the end of a meal."

On Rizal's first trip to Europe and student feasts

Rizal was born into a family of means; though his finances wavered at varying stages of his life, the man was fortunate to live in an age where international travel for middle-class Filipino academics was possible.

In describing a night out with fellow budget-minded Filipino students in Madrid, Spain, Sta. Maria writes, "the only time Rizal recorded 'pigging out' was during Carnival that year." With 14 friends, Sta. Maria continues:

They each paid one duro (the Spanish currency equivalent to one Philippine peso) for a menu cooked by Estevan Villanueva that included fourteen pounds of rice, fried fish, five boiled chickens, and five pounds of pork cooked as adobo. They also ate a roast piglet that used up a duro and a half of their budget. 'Not even a piece of the bone was left [of it],' Rizal wrote.

For a group of fifteen hungry, homesick, driven and politically determined young men, the indulgence of one dinner prepared so far from its roots - yet steeped in its tradition of a true community gathering - meant that simply cooked kanin (steamed white rice), pritong isda (fried fish), nilagang manok (boiled chicken) and adobong baboy (pork stewed with vinegar) signified cause for real celebration.

Oh, and they enjoyed lechon (roast pig) too - because what is a feast without crackling?